Kishangarh painting in the present day

|

| Radha Krishan painting by Nihal Chand -1750 ca |

After Sawant Singh’s death, Kishangarh painting lost much

of its originality, and the bravura of Nihal Chand’s works

declined from ninteenth century onwards. Today, painters

are still working in Kishangarh, but the glory of that period

is lost. They are merely reproducing the paintings and

mixing the schools and producing a style of their own.

Very few have studied and retained various styles of

Rajasthani minature paintings. This art form is taught to

anyone without any restriction of religion or caste.

Nowadays, the natural dyes are replaced with poster

colours. The brushes originally made by the tail of a squirrel

and prepared by the artist himself is now forgotten. The materials for painting are easily available in the market

these days and because of the availability of sophisticated

paints and brushes the artists too have adopted new

methods.

PAHARI SCHOOL OF PAINTING

The Pahari School of painting originated in the Hill kingdoms of Himachal Pradesh, a mountainous region of North India, during the 17th-19th century. The most notable schools of art categorized as Pahari include Basohli, Mankot, Nurpur, Chamba, Kangra, Guler, Mandi, and Garhwal. Many paintings from these schools were done in miniature form.

The Pahari School flourished from Jammu to Almora in the sub-Himalayan India, through Himachal Pradesh, each region producing unique variations within the genre. Perhaps the most famous, or at least the most prolific school, was that of the Kangra School, from which came an extensive range of delicate and beautifully detailed paintings.

The Kangra School became widely popular with the advent of Jayadev's Gita Govinda, of which many extant manuscripts feature exquisite Kangra illustrations. This style was copied by the later Mughal painting, many of whom were patronized by the Rajput kings who ruled various parts of the region. In part two, we will explore the Kangra School in some detail.

While perhaps not as well known as the Kangra School, but equally stunning is the Basohli School, which produced intensely brilliant canvases originating from the Basohli region of Jammu and Kashmir. Just as the Jammu/Kashmiri artists are well-known for their riotously bright colors, particularly primary reds and blues, the Basholi School paintings are equally brilliant, albeit more earth-toned.

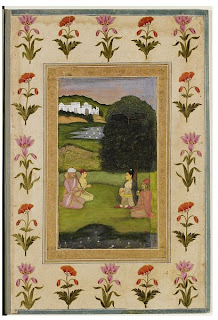

|

Radha and Krishna in Discussion

Gita Govinda Illustration, Basholi School, c. 1730 |

The Basohli School originated in the town of Gasholi in the Kathua district of Jammu and Kashmir state. Considered by many to be the first school of Pahari paintings, the Basholi style evolved into the very prolific Kangra school by the mid-18th century.

The Basholi style of painting is characterized by a strong use of primary colours, as well as by the peculiar style of facial depiction that prevailed during the late 17th and early 18th centuries in the foothills of the Western Himalayas, in the Jammu and Punjab States. The earliest paintings in this style date to the time of Raja Kirpal Pal (1678-93).

The Basohli style spread to the Hill States of Mankot, Nurpur, Kulu, Mandi, Suket, Bilaspur, Nalagarh, Chamba, Guler and Kangra. Of these, the Chamba and Garhwal School styles are well developed, but are perhaps less familiar to devotional art lovers compared to Kangra or Basholi paintings.

The first mention of Basohli painting is in the annual report of the Archaeological Survey of India for the year 1921. Referring to acquisitions by the Central Museum in Lahore, Pakistan, the report states that "a series of old paintings of the Basohli School were purchased, and the Curator concludes that the Basohli Schools is possibly of pre-Moghul origin, and so called Tibeti pictures are nothing but late productions of this school".

|

Nala-Damayanti from Mahabharat, Pahari School

|

,_Kishangarh,_ca._1760._Madison_Avenue_gallery.jpg)